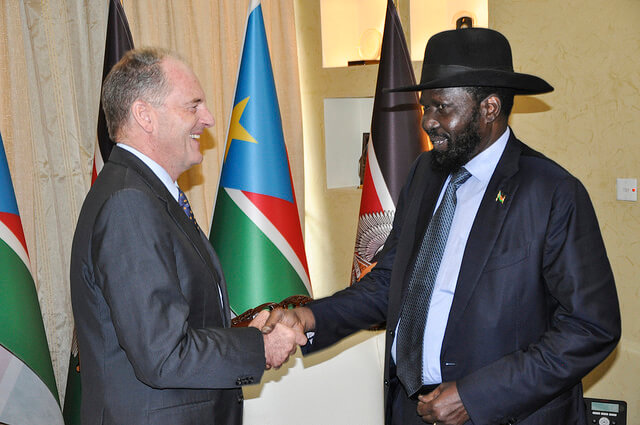

David Shearer at work in South Sudan where he heads the United Nations peace-keeping mission. All pictures courtesy of United Nations.

Former Mt Albert MP and Labour leader David Shearer talks to Bruce Morris about winning over his father, life in some of the world’s most dangerous hellholes and his tense final days as the head of the Labour Party.

To most of us, David Shearer is surely a strange animal. Why on earth would a smart, worldly-wise bloke choose to leave the family he loves in peaceful suburban Auckland for a risky hell-hole in Africa where respect for human life barely registers?

For an answer, the former Mt Albert MP and Labour Party leader, home last month on a break from the pressures of South Sudan, reaches back a couple of decades to a similar question posed by his dad.

They were at the airport and Mr Shearer Snr, anxious about his son’s humanitarian mission to warring and starving Somalia, said in sadness: “I just don’t understand why you do this.” It wasn’t a criticism – simply a poignant search for understanding from a dad to his son.

David Shearer didn’t have the words to ease his father’s anxiety, or that of his mum at his side. But, upset at the sad parting, he began a heartfelt letter home as soon as he took his seat on the plane. He used a phrase which was vivid then but has since been cheapened by over-use: “I have always wanted to make a difference.”

Today, it sounds almost corny, and whether it helped his dad’s understanding of the huge African job (in charge of feeding tens of thousands of very young starving children in aid centres across Somalia) wasn’t clear at the time.

But the deeply-felt message obviously registered. When it became really tough in Somalia, with the world looking elsewhere, a depressed David Shearer called his old man and unloaded some of his frustrations. This father responded as fathers do – standing up for his boy with a barrage of letters and calls to those in high places.

But the deeply-felt message obviously registered. When it became really tough in Somalia, with the world looking elsewhere, a depressed David Shearer called his old man and unloaded some of his frustrations. This father responded as fathers do – standing up for his boy with a barrage of letters and calls to those in high places.

Over time, any doubts disappeared and today, David Shearer says his father went on to become “my greatest supporter”.

His parents are no longer alive, though he was thrilled they were able to join him in London when the Queen made him a member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his work in Somalia. Shortly afterwards, he and his wife, Anuschka, were named the Herald’s New Zealanders of the Year.

His philosophy today is no different as head of the United Nations peace-keeping mission in South Sudan.

“I have always wanted to make a difference and I can honestly say that in the things I have done I have always tried to do so,” he told Mt Albert Inc before flying back to Africa after two weeks in New Zealand with Anuschka and their children, Vetya and Anastasia. “It has been immensely satisfying.”

Besides, says one of the UN’s top trouble-shooters, it’s not all that bad.

The 60-year-old spends much of his time in a huge protected compound in the capital of Juba. Whenever he moves, even if only to go for a jog within the guarded perimeter, he is accompanied by a band of heavily-armed personal security officers.

“Look, it’s hardly like living in a monastery. A lot of the time it can be fun. There are 125 different nationalities [in the general peace-keeping force] and on Fridays, we have a bar night – grass huts, music, the works. Everyone has a beer, listens to music, gets up dancing – to everything from African to Brazilian music to hip-hop.

“You can be in a group of a dozen to 20 people and none of them will be from the same country. They are all part of the UN, all part of the team I lead, and that is pretty cool.”

Cool is not a word that is often used in South Sudan, where temperatures are generally in the high 30s and the peace-keeping task, involving 19,000 troops and mission staff, is laced with risk and danger. It all falls under David Shearer’s control.

The aim is to inch towards peace, protecting the people as much as possible in a logistically impossible country and bringing the warring factions to the table… with their AK47s staying outside.

South Sudan is one of the world’s youngest nations, with a president and ruling party using their military power to keep splinter opposition armed forces at bay.

South Sudan is one of the world’s youngest nations, with a president and ruling party using their military power to keep splinter opposition armed forces at bay.

Caught up in the middle are ordinary people, who search for security around far-flung UN bases or over the border – two million of them – in surrounding countries such as Kenya, Uganda, Sudan and Somalia… waiting for peace before returning to their sacked villages.

It will be a long wait, but Mr Shearer reports that talks are showing some promise. It is a very slow process and can be sabotaged at any time; as Syria illustrates, where a ruler thinks he is winning militarily, why would he want to compromise?

The humanitarian veteran, reporting to the UN Secretary-General, has a “glass-half-full” approach and says an endless emphasis on the mission’s aim – building peace and protecting civilians – helps to bring focus: “The more we build peace, the more we are able to protect civilians.”

When people ask, “What’s the point?”, he has a ready answer: “If we weren’t there, thousands more would be dead. For that reason I wake up every morning and don’t have a problem about starting my day.”

He has introduced a three-word catch-phrase and drilled it into his military commanders: “Robust, nimble, proactive.” No standing back allowing South Sudan forces of all shades to do as they like, making life miserable – and short – for so many.

The result, he feels, has been big progress in a land where tribal disputes frequently led to deadly clashes.

“Our troops used to sit in their bases, but now they are out there, in the villages. And the village people who were thinking of moving away to safety, well, they have that added security and are able to remain where they are, growing food, establish their own connections and keep together. We have made big progress.”

But it’s not just soldiers who are helping to tame South Sudan. David Shearer’s leadership has focused also on peace-keeping at a local level, where UN civic affairs staff unravel problems in the villages.

“This is invisible work because it never gets any attention,” he says. “It’s unsung – like bringing two tribes together after an outbreak of violence where people have been killed, settling things down, or negotiating with cattle herders so they don’t move through areas with crops and ruin them.”

“This is invisible work because it never gets any attention,” he says. “It’s unsung – like bringing two tribes together after an outbreak of violence where people have been killed, settling things down, or negotiating with cattle herders so they don’t move through areas with crops and ruin them.”

These sorts of disputes used to be settled with spears, but now it’s AK47s: more than 30 people were killed in a squabble just before Christmas. Having staff on the ground is vital to getting combatants to sit down and negotiate before tensions turn into violence.

The UN Security Council has published a new mandate outlining its expectations for the peace-keeping mission, and Mr Shearer has had his term extended for another year. He knows there will be no settled peace and free elections in his time, but is confident these will come.

“I worked in Liberia in the 90s when people were being murdered in the streets – where, under some black-magic guise, chests were cut open and hearts were eaten. Yet at the end of this month, peace-keepers will pull out of Liberia… In Sierra Leone, people once got their hands cut off for daring to vote, but they have just had free presidential elections.

“There are still lots of problems in those countries, but there has been great progress and the same can happen in South Sudan. You just have to keep reminding yourself that this is not going to happen in a short period of time.”

He certainly is not there for the long haul, even if the UN wants him to be. “I have always found that the longer you stay in a place, two things happen: you become more knowledgeable and, at the same time, you become jaded and your credit with the people you’re working with starts to run down.

“At some point you say, ‘Well, I’m going OK but it probably needs someone else to come in and take it forward. I haven’t got to that point, but you’ve got to be really honest with yourself.”

So, what’s next after South Sudan?

He doesn’t have anything in mind, but figures something will crop up.

“There are an enormous number of opportunities out there and you need to grab them. The problem is that a lot of people don’t see them as opportunities. They see things in terms of whether an opportunity will be a burden or a hassle or just not the right time… instead of stepping off the edge and having a crack.”

He certainly knows he won’t return to politics. In the unlikely event that Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern invited him back, he might be tempted to say, “Souffles rarely rise twice.”

“I gave it my best shot and in some ways when I left, Labour looked like it was unlikely to win, and it did and it’s great. But I wouldn’t trade what I have now to come back to politics.

“Yes, it would have been great to be a minister, and I would have loved to be minister of foreign affairs. But I don’t have any regrets – you always regret what you don’t do rather than what you do. If I hadn’t jumped in, I might later have wondered, ‘Why didn’t I have a shot?’ Well, I had a shot, gave it my best shot and it just about killed me.”

Mr Shearer said he got to the point, about two months before he resigned as Labour Party leader, where he decided “I was listening to too much advice from people who had been around politics much longer than I had. No, bugger it, I thought. I’m not listening to others anymore. I’m going to start doing it myself. The polls started going up and I started feeling more confident about myself.

“By that stage there was enough of a kind of organised dissent against me… Actually, to be honest, they could see the thing was going up and I believe it’s one of the reasons that they ended up moving on me – because they could see if they didn’t do it then, it wasn’t going to happen… I was going to go into the next year and through to the election as leader.”

He feels his politics were “where New Zealand kind of sat – mainstream New Zealand, and I think John Key did that as well. But that was way too off-beam for some of the people in my party who were way over to the left… and you don’t win elections over there. You win them in the centre”.

Through it all, though, he says he maintained his position on the things he felt mattered – equality, a living wage and a more innovative future for New Zealand.

Of course, in South Sudan, Mr Shearer misses his family, though Skype and WhatsApp help to bridge the gap. A family holiday in Europe last year (with another in the planning this year) and two or three trips back to New Zealand are great boosts until he decides it’s time for a new challenge.

He also misses Mt Albert, and savours the time he spent most Saturday mornings on the electorate’s sporting fields, talking to locals and getting a feel for their problems and issues. As a former teacher, he also loved his time visiting the great local schools.

Compared to the violence, hunger, dust and poverty of the African nation, the tree-lined streets of Mt Albert must seem like a mirage. But for a guy who is in life to make a difference, he knows where he would rather be right now.

David Shearer meets South Sudan’s President Kiir. Picture: UN